Neighborhood deprivation linked to longer hospital stays after children's surgery

Children from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods tend to spend more time in the hospital after surgery, even when their complication rates are similar to those of other children, according to a large, multi-state study using national administrative data.

The study was led by CHEAR faculty investigator Samir Gadepalli, MD, MS, MBA, and recently appeared in The American Journal of Surgery.

Previous single-center studies have suggested that neighborhood deprivation can contribute to delays in care and worse postoperative outcomes for children, according to Gadepalli. To better understand whether these patterns hold across diverse settings, the research team analyzed generalizable data from State Inpatient Databases.

The study examined 102,399 children who underwent six common surgical procedures and assessed neighborhood deprivation using the Child Opportunity Index, a composite measure of neighborhood-level social and economic conditions. Researchers compared risk-adjusted hospital length of stay (LOS) and postoperative complication rates using multivariable regression models.

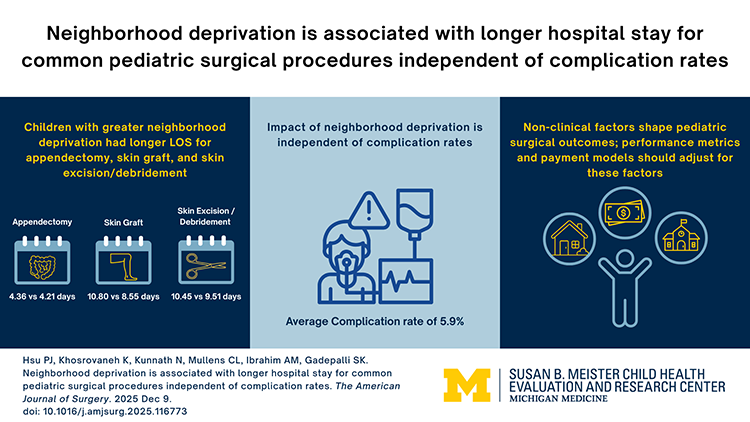

Children from more deprived neighborhoods were more likely to be from racial and ethnic minority groups, have public insurance, and be transferred from another facility for care. After adjusting for clinical risk factors, neighborhood deprivation was associated with longer hospital stays for several procedures, including appendectomy, skin grafting, and skin excision or debridement. For example, children undergoing appendectomy from the most deprived neighborhoods stayed an average of 4.36 days compared with 4.21 days for those from the least deprived areas.

Importantly, complication rates did not differ by neighborhood deprivation. The longer lengths of stay also persisted among children who experienced no complications, suggesting that non-clinical factors may be influencing postoperative utilization.

The authors concluded that while surgical outcomes appear similar, children from deprived neighborhoods require longer hospital stays, pointing to social and structural factors beyond direct medical care. These findings highlight the need for payment models and quality metrics to better account for social determinants of health, ensuring that hospitals caring for more disadvantaged populations are not unfairly penalized for factors outside their control.

"If you come from a neighborhood that's harder, where you don't have resources available to you, what we found is that you stay in the hospital longer," Gadepalli said. "It's not because the care was any different. If you were up in Marquette (Mich.) and you came to University of Michigan to get your appendix removed, it's not because you were more likely to have a complication or more perforation or a delayed presentation or any of these things. It's actually because we're afraid to send you back home until things are more perfect than they would be if you lived in Ann Arbor."